Information for operations on the aortic valve

Content:

|

Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Homburg/Saar |

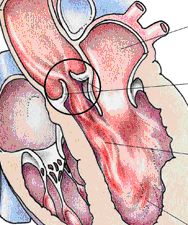

The aortic valve is the outlet valve of the left ventricle which generates the main energy that keeps the blood circulating through the body. The valve is supposed to open as completely as possible during ejection of the blood in order to avoid unnecessary loss of energy. While the left ventricle is filling with blood from the left forechamber and lung veins the valve should be closed to avoid backflow of blood from the aorta into the left ventricle. If the valve does not open completely it is called stenosed (narrowed), if it does not close completely during the filling phase the valve is regurgitant (leaking).

Stenosis of the aortic valve leads to thickening of the heart muscle, at a later stage the blood supply to the thickened heart muscle may be inadequate. Thickening and suboptimal blood flow may lead to changes of the heart muscle of the left pumping chamber that persist despite correction of the valve problem. Regurgitation (leak) leads to additional load of the left ventricle through the blood that flows back into the ventricle during the filling phase. As a consequence the heart chamber increases in size and muscle thickness. The result is a combination of muscle being overworked and not receiving adequate blood supply, which may lead to persistent damage of the heart muscle.

Both types of function problems may be associated with a stable situation over many years. During this phase the heart adapts to the functional problem and maintains blood supply to the body. Once certain symptoms or alterations occur the heart cannot compensate the valve problem and there is an increasing possibility of developing heart failure and ultimate death. At this time the valve problem has to be treated, and at this time a valve operation is the only possible treatment. It is the goal of the operation not to be too early, but also not to be too late in order to avoid persistent damage of the heart muscle.

Typical signs are: decreasing exercise tolerance, increasing fatigue or shortness of breath, or chest pain. There are also specific changes that can be determined by an ultrasound study of the heart, such as decreased pumping force or marked enlargement of the left ventricle. Your physician can best judge which of these symptoms is most important in your situation. The ideal solution would restore valve function fort he rest of the life and not have side effects. Unfortunately we do not yet have this ideal valve operation. There are several different possibilities. Each possibility has specific advantages and disadvantages, and we will need to find the best solution for your specific situation. You will find a summary of all possibilities even though not all may be reasonable in your specific case.

Mechanical valve replacement

Mechanical valves of current design were developed in the 1970s. They are made out of carbon (graphite) that changes its properties under high pressure and high temperatures and becomes a hard and durable material. This carbon is currently the best synthetic material for heart valves but still not ideal.

The durability of these valves is probably more than 40 years. On the other hand blood clots may form on the foreign surface of the valve, and these blood clots may be dislodged into blood vessels of the body or brain, or they may even block the valve. In order to minimize the formation of blood clots it is necessary to take medication that blocks the coagulation system of the blood, and this medication has to be taken lifelong (Coumadin, warfarin). The most important side effect of these drugs is the occurrence of bleeding problems that may happen as a consequence of trauma or even without a trauma. It is important and necessary to monitor the effect of the “blood thinners” carefully in order to keep the combined possibility of clot formation and bleeding problems at a minimum. With careful surveillance the risk of developing either a clot or a bleeding problem is in the range of 3 to 3.5% per year.

In certain situations (e.g. major dental procedures) bacteria may get into the blood stream, settle on the artificial heart valve, and cause a bacterial infection of the valve (so-called endocarditis). The likelihood of developing an endocarditis is approximately 1% per year, and these serious complications not only requires aggressive treatment with antibiotics, but also repeat replacement of the valve in an operation. Blockage of the valve is rare but also has to be treated by a repeat operation. Looking at a period of 15 years, the probability of valve-related complications is approximetaly 4 to 5% per year, and the likelihood of a second operation is 1% per year.

Biologic valve replacement

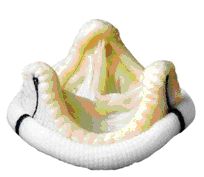

Biologic heart valves have existed since the 1970s. They are either specially prepared aortic valves of pigs or they are made out of pericardial tissue of cows. The animal tissue is prepared in such a way that it can be stored for years and maintains its form and function after implantation into the human body for as many years as possible. This preservation treatment also makes it unrecognizable as foreign tissue to the human body, so it cannot be rejected (as would happen if normal tissue or organs are implanted / transplanted). Therefore it is not necessary to take anti-rejection medication (immunosuppression).

Most biologic heart valves are mounted onto stents that stabilize their form and make implantation easy. More than 10 years ago so-called stentless heart valves were developed. They have a slight advantage in valve function, but it is still uncertain whether their durability is better than that of conventional biologic valves.

The tendency to develop clot formation with biologic valves is low, and treatment with specific blood thinners is recommended for only 3 months as long as heart rhythm is stable. Some cardiologists and cardiac surgeons recommend life-long intake of low-dose aspirin (100 mg per day) in order to keep the likelihood of clot formation low. Blockage of the valve with clots does not occur, the risk of bacterial infection (endocarditis) is identical to that of mechanical valves (appr. 1% per year).

The durability of biologic valves is principally limited because of degeneration (wear) of the valves. The time until the valve wears out is related to the age of the patient and increases with age. In young patients (<25 years) the mean durability is 7 to 8 years, in a 50 year-old about 12 to 13 years, and in a 70 year-old more than 20 years. When the valve is worn out a repeat operation or intervention is necessary. In the future a catheter-based intervention may be an alternative to a typical operation. The risk of a repeat operation depends on individual risk factors, in general it is only slightly higher than that of the first valve operation.

Looking at a period of 15 years the risk of valve-related complications in a middle-age patient (55 to 60 years) is about 4 to 5% per year with degeneration as the most important complication. Your physician can give you a personalized estimate.

Valve replacement using a transcatheter valve

In the past few years a new technology has been developed in order to minimize the trauma of insertion of a heart valve. For this purpose biologic valves have been modified to be mounted on a stent, i.e. a wire mesh. These valves are inserted using a catheter and therefore called “transcatheter valves” (TAVI). The catheter may be passed from the leg artery in the groin (femoral artery) to the heart. Alternatively, a small incision is made on the chest and the catheter is passed from the tip of the left ventricle to the aorta. The valve is then brought into the desired position and anchored there.

At this time the procedure is still new, and we have very limited information on the stability of these new valves (less than 5 years). It is still unproven whether the risk of insertion is lower compared to a conventional operation. On the other hand there may be specific situations in which this procedure can be expected to be an advantage to the patient. Generally the valve should not be used in younger patients because of the uncertain stability. An individualized decision will be necessary, and your physician may be able to give you a recommendation based on your specific and individual situation.

Valve replacement with the valve of the pulmonary artery (Ross-Operation)

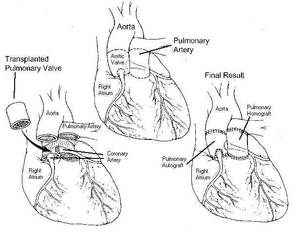

This form of aortic valve replacement was first developed in 1967 by the English surgeon Donald Ross, and it is therefore frequently called “Ross-Operation”. The operation takes advantage of the fact that the design of the valve in the lung artery (pulmonary artery) is identical to that of the aortic valve. The pulmonary valve is carefully taken out of the right ventricle and then implanted instead of the diseased aortic valve. Either a human or a tissue valve is then inserted between right ventricle and pulmonary artery in order to normalize the structure of the heart and vessels. Since the pressures in the pulmonary artery are much lower than those in the aorta the durability of the valve inserted in the pulmonary artery is much higher than it would be in the aorta.

The tendency to develop clot formation with this operation is minimal. We usually recommend to take aspirin (100 mg per day) for the first 2 months after the procedure. Blockage of the valve from clots does not occur, and the risk of endocarditis is lower compared to mechanical or tissue valves ( 0,2% per year).

The durability of the pulmonary valve that has been inserted into the aorta is good, and particularly in young patients statistically much longer than that of biologic valves. Unfortunately slight alterations in its form or enlargement in its connection to heart or aorta can lead to the development of a leak and ultimately a repeat operation. The durability of the valve that is used for the connection of the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery is principally limited. Here the same principle applies as for biologic replacement of the aortic valve that durability increases with age, even though durability is generally higher. Ultimately a repeat procedure will be necessary, either as an operation or as insertion of a catheter-based valve.

Over a 10-year period the likelihood of valve-related complications is less than 2% per year, with degeneration of leak of either valve being the most important event. A disadvantage of this procedure is its complexity compared to other operations, in part due to the fact that 2 valves are operated upon in order to treat 1 diseased valve.

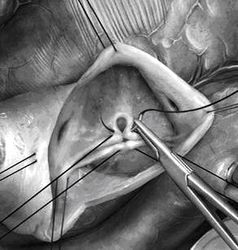

Reconstruction of the aortic valve

|  |

This alternative to replacement is the youngest treatment form and is mostly applicable in aortic regurgitation (leak). Reconstruction is not a standard procedure that is identical in all instances, but rather aims at normalizing the form of the individual valve and thus eliminates its functional problem. Most techniques have been developed over the past 15 years. Either a valve abnormality or enlargement of the aorta (or both in combination) leads to the valve leak. In each patient the abnormalities must be carefully analyzed in order to develop a repair strategy.

If the main blood vessel (aorta) is enlarged the affected part is replaced with a segment of prosthetic “hose”, and the aortic valve is then adapted to the new dimensions. There are also techniques to correct the enlarged transition between left ventricle and aorta. If the valve elements (cusps) are stretched this can be corrected by shortening the structure with sutures. Defects that may be the consequence of a previous heart valve infection can be closed with patches from pericardium. Special configurations that have been present since birth will require correction using specific techniques that create a valve form which will lead to reproducible function.

Your physician will be able to explain the type of procedure that you need based on the images of a transesophageal echocardiogram. The final decision, however, will have to be made in the operating room.

At this time we have the longest experience with operations in which the leak of the aortic valve is caused by enlargement of the aorta. In the past 15 years repair techniques have also been developed for other causes of leaking aortic valves.

After reconstruction of the aortic valve the possibility of clot formation is minimal. We recommend Aspirin (100 mg per day) for the first 2 months postoperatively, later no blood thinners are necessary for the valve. Blockage of the valve with clot does not occur. The risk of bacterial infection (endocarditis) is lower than that after implantation of a mechanical or biological prosthesis (approximately 0,2% per year).

The durability of the reconstructed valve depends on its form (anatomy) and specific details that are found at the time of operation. Especially in young patients the stability is usually longer than that of a biological prosthesis, maybe even comparable to that of the Ross operation. The likelihood of valve-related complications over a 10 to 15 year period is less than 2% per year. The most important event would be recurrence of the leak.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no ideal solution (yet). It is therefore important to find the best compromise for your problem. The mechanical solution will be associated with the lowest risk of reoperation long term, but there are the problems of clot formation and blood thinners. The biological prosthesis and the Ross operation will cause fewer problems while they work, but their durability is limited. Reconstruction is relatively new but quite apparently offers results similar to the Ross operation. Unfortunately no treatment is free from the risk of a repeat operation, and the time to the next operation is difficult to predict for the individual.

You should carefully consider all information and make certain that all questions are answered. You also have to know that unforeseeable information found during the operation may lead to a change in plan. This is particularly relevant for the Ross operation and reconstruction. In order to allow the surgeon to make the best decisions for you you should define a procedure of choice (plan A) and a “second best” (plan B).

Prof. Dr. med. H.-J. Schäfers, 04.01.2019